Shapes#

Imports#

import mumaxplus.util.shape as shapes

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import pyvista as pv

What are Shapes?#

In mumax⁺ you can use the util package to define shapes. Each shape is a mutable instance of the Shape class, which holds and manipulates a function. This shape function takes an (x, y, z) coordinate (in meters) and returns True if it lies within the shape. All methods called upon a shape will manipulate it. They can transform, translate or rotate the shape, or can combine it with other shapes using boolean operations. There are quite a few built-in shapes.

For example, here my_shape is defined to be a basic Circle with a diameter

of 2 (meters). To check if (0, 0, 0) or (1, 1, 0) lie within it, my_shape

can be evaluated directly like a function.

my_shape = shapes.Circle(2)

print("Is (0,0,0) within my_shape?", my_shape(0,0,0))

print("Is (1,1,0) within my_shape?", my_shape(1,1,0))

Is (0,0,0) within my_shape? True

Is (1,1,0) within my_shape? False

Plotting#

We’ll need some basic code to view the shapes. To pan around in the 3D PyVista plots, you might need to install some extra stuff (namely trame):

pip install ipywidgets 'pyvista[all,trame]'

def plot_shape_2D(shape, x, y, title="", ax=None):

"""Show a shape in the xy-plane at z=0, given x and y coordinate arrays. This uses matplotlib."""

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

S = shape(X, Y, np.zeros_like(X))

show_later = False

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

show_later = True

dx, dy = (x[1]-x[0]), (y[1]-y[0])

ax.imshow(S, extent=(x[0]-0.5*dx, x[-1]+0.5*dx, y[0]-0.5*dy, y[-1]+0.5*dy), origin="lower", cmap="binary")

ax.set_xlabel("x"); ax.set_ylabel("y")

ax.set_aspect("equal")

if len(title) > 0: ax.set_title(title)

if show_later: plt.show()

def plot_shape_3D(shape, x, y, z, title="", plotter=None):

"""Show a shape given x, y and z coordinate arrays. This uses PyVista."""

X, Y, Z = np.meshgrid(x, y, z, indexing="ij") # the logical indexing

S = shape(X, Y, Z)

dx, dy, dz = (x[1]-x[0]), (y[1]-y[0]), (z[1]-z[0])

# [::-1] for [x,y,z] not [z,y,x] and +1 for cells, not points

image_data = pv.ImageData(dimensions=(len(x)+1, len(y)+1, len(z)+1),

spacing=(dx,dy,dz), origin=(x[0]-0.5*dx, y[0]-0.5*dy, z[0]-0.5*dz))

image_data.cell_data["values"] = np.float32(S.flatten("F"))

threshed = image_data.threshold_percent(0.5) # only show True

show_later = False

if plotter is None:

plotter = pv.Plotter()

show_later = True

plotter.add_mesh(threshed, color="white", show_edges=True, show_scalar_bar=False, smooth_shading=True)

plotter.show_axes()

if len(title) > 0: plotter.add_title(title)

if show_later: plotter.show()

def plot_shape(shape, x, y, z=None, **kwargs):

if z is None:

return plot_shape_2D(shape, x, y, **kwargs)

return plot_shape_3D(shape, x, y, z, **kwargs)

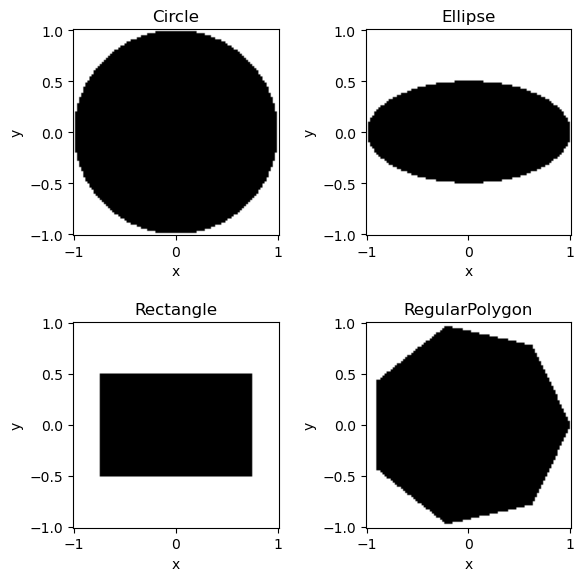

Built-in Shapes#

Here are a few examples of basic shapes. They can be initialized like any other instance of a class, with the approprate variables. Usually one or more diameters, not radii, are expected.

2D Shapes#

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(6, 6))

x, y = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100), np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

my_shapes = [shapes.Circle(2), shapes.Ellipse(2, 1), shapes.Rectangle(1.5, 1), shapes.RegularPolygon(7, 2)]

for shape, ax in zip(my_shapes, axes.flatten()):

plot_shape_2D(shape, x, y, title=shape.__class__.__name__, ax=ax)

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

2D shapes are best defined in the xy-plane, but they exist in 3D aswell. The z-coordinate is simply ignored, so they extend indefinitely in the z-direction.

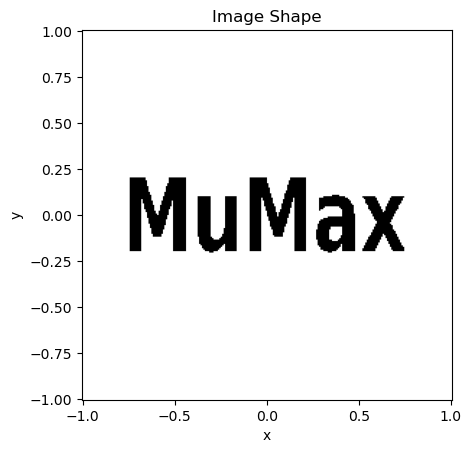

ImageShape#

A black and white image can also be used as a shape. Black is interpreted as inside (True), white as outside (False). The centers of the bottom left and top right pixels are mapped to the given x and y coordinates.

img_shape = shapes.ImageShape("shape.png", (-0.75, -0.2), (0.75, 0.2))

x = y = np.linspace(-1, 1, 256)

plot_shape(img_shape, x,y, title="Image Shape")

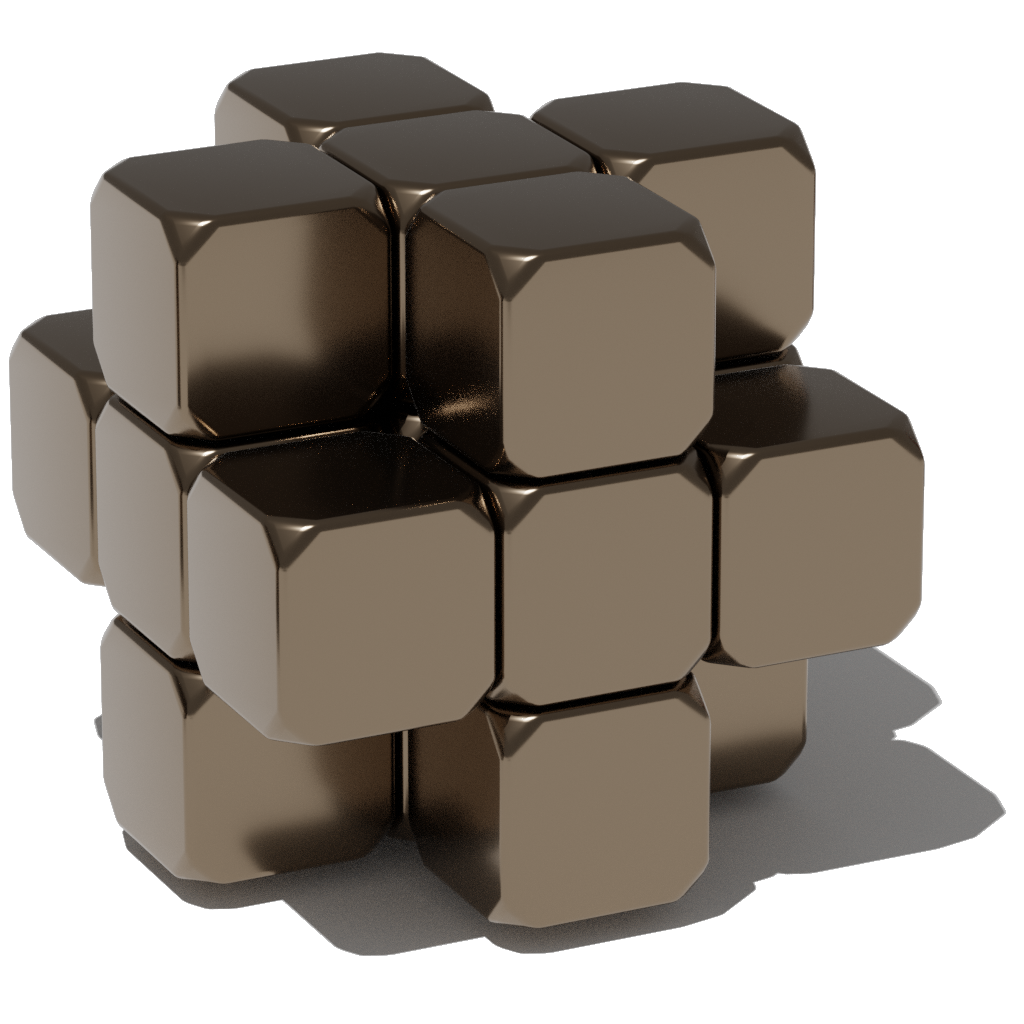

3D Shapes#

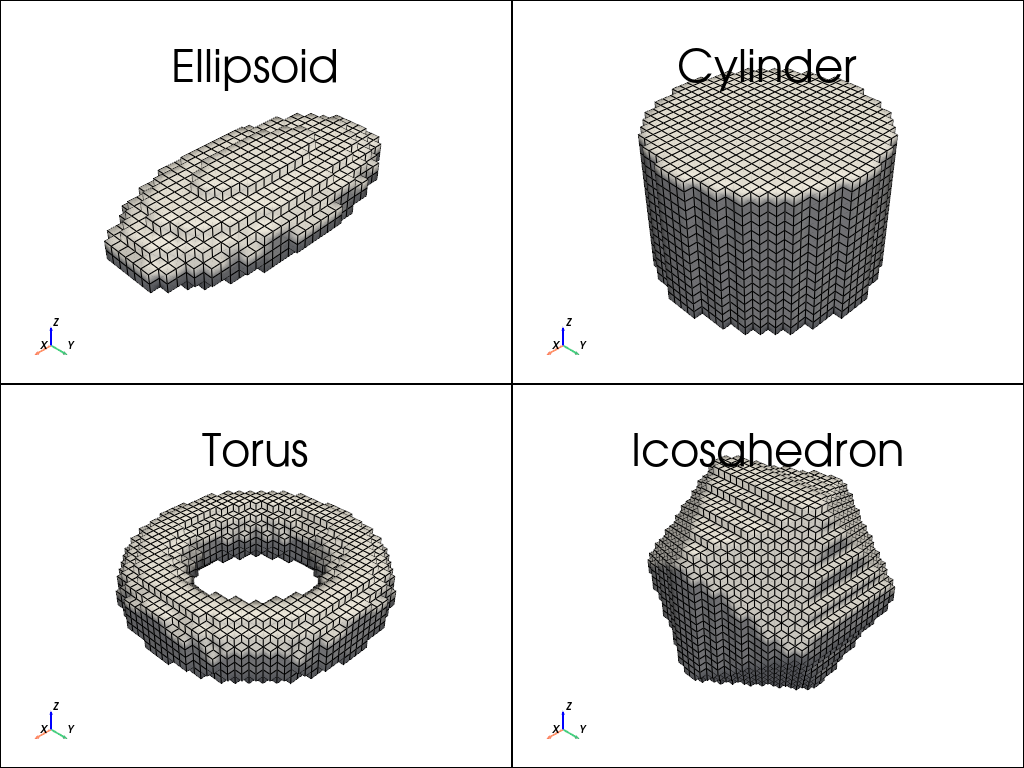

plotter = pv.Plotter(shape=(2,2))

x = y = z = np.linspace(-1, 1, 32)

my_shapes = [shapes.Ellipsoid(2, 1, 0.5), shapes.Cylinder(1.5, 1), shapes.Torus(1.5, 0.5), shapes.Icosahedron(2)]

for i, shape in enumerate(my_shapes):

plotter.subplot(i//2, i%2)

plot_shape_3D(shape, x, y, z, title=shape.__class__.__name__, plotter=plotter)

plotter.show()

All shapes are classes in mumaxplus.util.shape, which has been imported as “shapes” above. Hence, all built-in shapes can be found by

import mumaxplus.util.shape as shapes

print(dir(shapes))

['Circle', 'Cone', 'Cube', 'Cuboid', 'Cylinder', 'DelaunayHull', 'Dodecahedron', 'Ellipse', 'Ellipsoid', 'Empty', 'Icosahedron', 'Icosidodecahedron', 'ImageShape', 'Octahedron', 'Polygon', 'Rectangle', 'RegularPolygon', 'Shape', 'Sphere', 'Square', 'Tetrahedron', 'Torus', 'Universe', 'XRange', 'YRange', 'ZRange', '_Delaunay', '_Image', '_Path', '__builtins__', '__cached__', '__doc__', '__file__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', '_np']

Transformations#

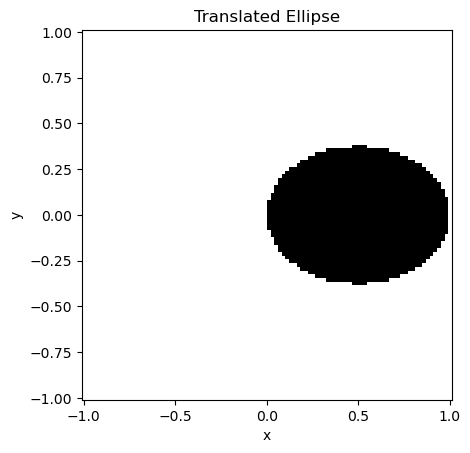

A shape has methods to transform it. These will modify the shape on which they are called. The simplest example is a translation.

my_ellipse = shapes.Ellipse(1, 0.75)

my_ellipse.translate_x(0.5)

x = y = z = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

plot_shape(my_ellipse, x, y, title="Translated Ellipse")

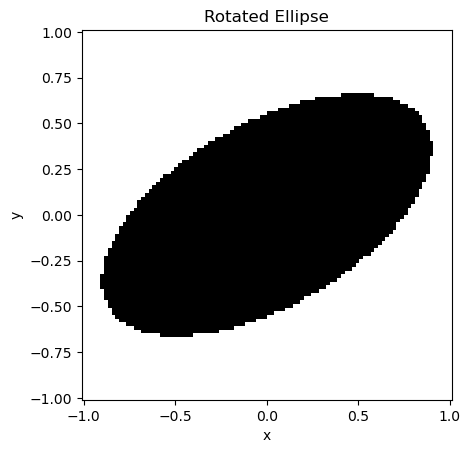

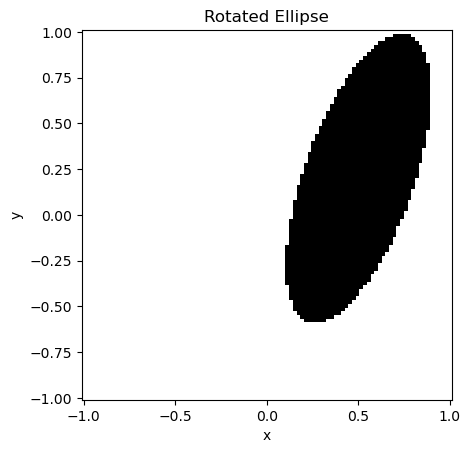

translate_y, translate_z and translate also exist. Another transformation

is the counter-clockwise rotation around a given axes in radians, such as

rotate_x, rotate_y and rotate_z.

my_ellipse = shapes.Ellipse(2, 1)

my_ellipse.rotate_z(np.pi/6)

x = y = z = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

plot_shape(my_ellipse, x, y, title="Rotated Ellipse")

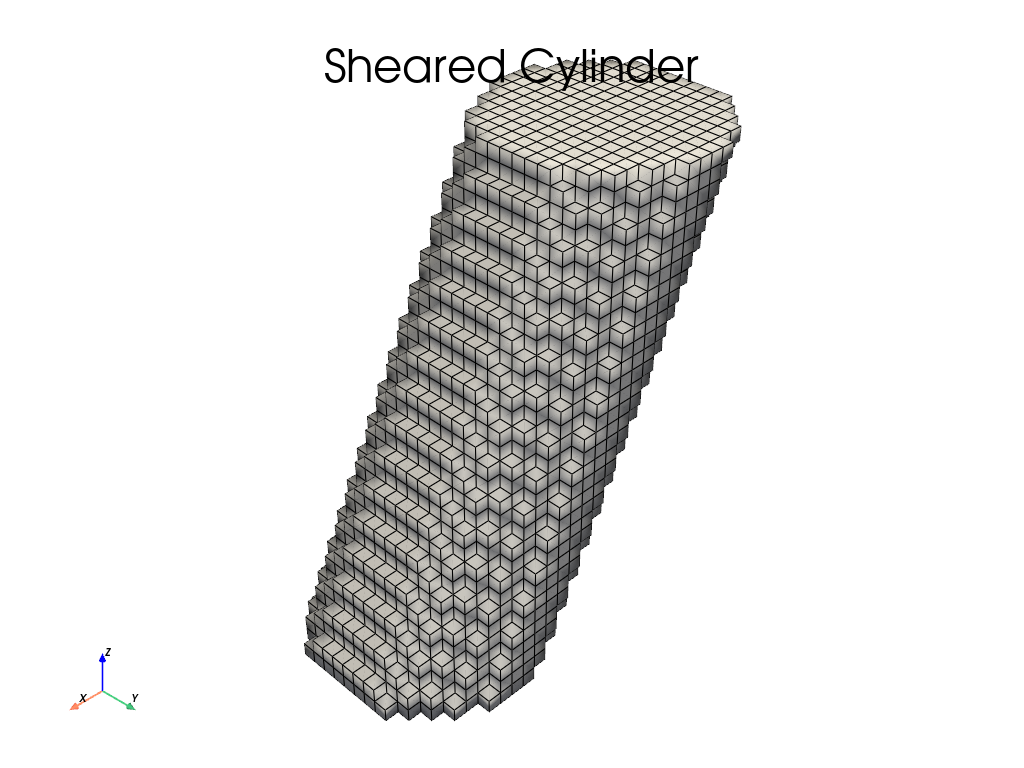

There are even more transformations, like scale, mirror and repeat, which

are fairly self-explanatory. In general a \(3 \times 3\) or even

\(4 \times 4\) transformation matrix can be passed to get any affine

transformation. As an example, here is a sheared cylinder.

Note

The inverse transformation will have to be used, as the coordinates

(x, y, z) are transformed (passive transformation) and not the shape itself

(active transformation). For example, a doubling in volume is achieved by

dividing the coordinates by two: np.diag([1/2, 1/2, 1/2]).

my_cylinder = shapes.Cylinder(1, 2)

shear_matrix = np.array([[1, 0, 0.5],

[0, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 1]])

my_cylinder.transform3(shear_matrix)

x = y = z = np.linspace(-1, 1, 32)

plot_shape(my_cylinder, x, y, z, title="Sheared Cylinder")

Multiple transformations can be chained together. This is possible because every transformation returns the shape itself. They are executed from left to right, like normal Python methods.

my_ellipse = shapes.Ellipse(1, 0.5).rotate_z(45*np.pi/180).scale(1, 2, 1).translate(0.5, 0.2, 0)

x = y = z = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

plot_shape(my_ellipse, x, y, title="Rotated Ellipse")

Combining Shapes#

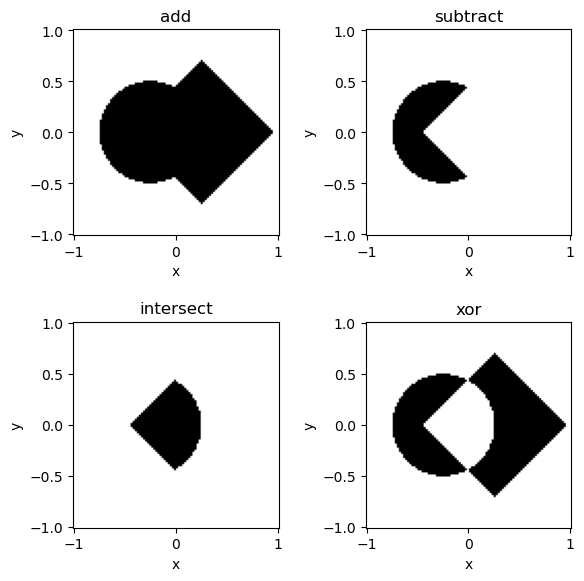

Because every shape is a function returning a boolean (True or False), multiple shapes can be combined using boolean operations (and, or, not, xor). This is a technique called Constructive Solid Geometry (CSG).

circle = shapes.Circle(1).translate_x(-0.25)

square = shapes.Square(1).rotate_z(45*np.pi/180).translate_x(+0.25)

add = circle + square

sub = circle - square

intersect = circle & square

xor = circle ^ square

fig, axs = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(6,6))

x = y = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

plot_shape_2D(add, x, y, title="add", ax=axs[0,0])

plot_shape_2D(sub, x, y, title="subtract", ax=axs[0,1])

plot_shape_2D(intersect, x, y, title="intersect", ax=axs[1,0])

plot_shape_2D(xor, x, y, title="xor", ax=axs[1,1])

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

These operations all return a new Shape instance. If you want to modify the shape

directly, you can use the methods, like add, sub, intersect and xor. You

can also use inplace operators, such as +=, -=, &= and ^=.

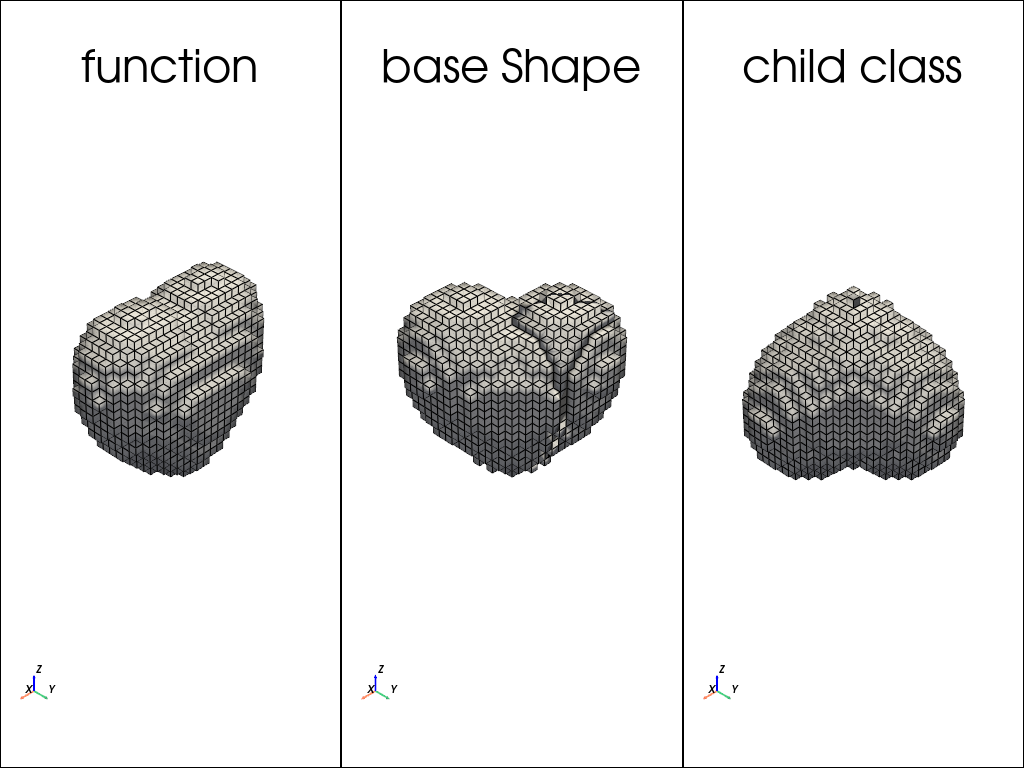

Make your own shape#

You don’t need to define a shape for the purposes of defining the geometry of a

magnet. A simple function will suffice. But if you want to take advantage of the

implemented Shape methods, that’s possible. You can use the base Shape class

and give it a function. If you want to use it more often, perhaps consider making

a new child class.

# A) a simple function

def heart_function(x,y,z):

return (x**2 + (9/4)*(y**2) + z**2 - 1)**3 - (x**2)*(z**3) -(9/200)*(y**2)*(z**3) <= 0

# B) a base Shape class instance with a custom function

heart_shape_inst = shapes.Shape(heart_function)

# C) a Heart child class instance

class Heart(shapes.Shape):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__(heart_function)

heart_class_inst = Heart()

# slight transformations to keep it interesting

heart_shape_inst.rotate_z(-45*np.pi/180)

heart_class_inst.rotate_x(np.pi).rotate_z(-45*np.pi/180)

# plotting

plotter = pv.Plotter(shape=(1,3))

x = y = z = np.linspace(-1.5, 1.5, 32)

plotter.subplot(0,0)

plot_shape(heart_function, x, y, z, title="function", plotter=plotter) # simple function

plotter.subplot(0,1)

plot_shape(heart_shape_inst, x, y, z, title="base Shape", plotter=plotter) # base Shape instance

plotter.subplot(0,2)

plot_shape(heart_class_inst, x, y, z, title="child class", plotter=plotter) # child Heart instance

plotter.show()

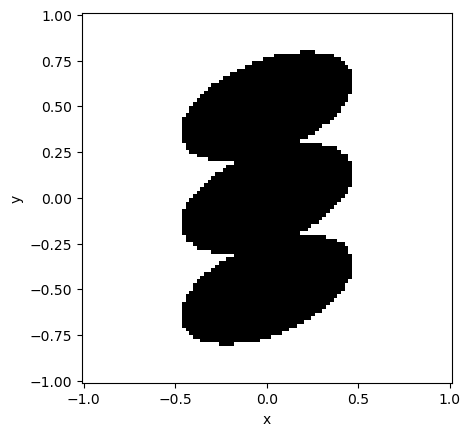

Copy#

Lastly, if you ever want to use a shape in two different ways, you can copy it

using the .copy() method.

my_shape = shapes.Ellipse(1, 0.5)

my_shape.rotate_z(np.pi/8)

top_shape = my_shape.copy().translate_y(0.5) # translate a copy up

bottom_shape = my_shape.copy().translate_y(-0.5) # translate a different copy down

total_shape = my_shape + top_shape + bottom_shape

x = y = np.linspace(-1, 1, 100)

plot_shape(total_shape, x, y)